Hawaii

Description

Hawaii ee; locally, Hawaiian: Hawaiʻi [həˈvɐjʔi]) is the 50th and most recent state of the United States of America, receiving statehood on August 21, 1959. Hawaii is the only U.S. state located in Oceania and the only one composed entirely of islands. It is the northernmost island group in Polynesia, occupying most of an archipelago in the central Pacific Ocean. Hawaii is the only U.S. state not located in the Americas. The state does not observe daylight saving time.

The state encompasses nearly the entire volcanic Hawaiian archipelago, which comprises hundreds of islands spread over 1,500 miles (2,400 km). At the southeastern end of the archipelago, the eight main islands are—in order from northwest to southeast: Niʻihau, Kauaʻi, Oʻahu, Molokaʻi, Lānaʻi, Kahoʻolawe, Maui and the Island of Hawaiʻi. The last is the largest island in the group; it is often called the "Big Island" or "Hawaiʻi Island" to avoid confusion with the state or archipelago. The archipelago is physiographically and ethnologically part of the Polynesian subregion of Oceania.

Hawaii's diverse natural scenery, warm tropical climate, abundance of public beaches, oceanic surroundings, and active volcanoes make it a popular destination for tourists, surfers, biologists, and volcanologists. Because of its central location in the Pacific and 19th-century labor migration, Hawaii's culture is strongly influenced by North American and Asian cultures, in addition to its indigenous Hawaiian culture. Hawaii has over a million permanent residents, along with many visitors and U.S. military personnel. Its capital is Honolulu on the island of Oʻahu.

Hawaii is the 8th-smallest and the 11th-least populous, but the 13th-most densely populated of the fifty U.S. states. It is the only state with an Asian plurality. The state's coastline is about 750 miles (1,210 km) long, the fourth longest in the U.S. after the coastlines of Alaska, Florida and California.

Etymology

The state of Hawaii derives its name from the name of its largest island, Hawaiʻi. A common Hawaiian explanation of the name of Hawaiʻi is that was named for Hawaiʻiloa, a legendary figure from Hawaiian myth. He is said to have discovered the islands when they were first settled.

The Hawaiian language word Hawaiʻi is very similar to Proto-Polynesian *Sawaiki, with the reconstructed meaning "homeland". Cognates of Hawaiʻi are found in other Polynesian languages, including Māori (Hawaiki), Rarotongan (ʻAvaiki) and Samoan (Savaiʻi) . According to linguists Pukui and Elbert, "[e]lsewhere in Polynesia, Hawaiʻi or a cognate is the name of the underworld or of the ancestral home, but in Hawaii, the name has no meaning".

Spelling of state name

A somewhat divisive political issue arose in 1978 when the Constitution of the State of Hawaii added Hawaiian as a second official state language. The title of the state constitution is The Constitution of the State of Hawaii. Article XV, Section 1 of the Constitution uses The State of Hawaii. Diacritics were not used because the document, drafted in 1949, predates the use of the okina (ʻ) and the kahakō in modern Hawaiian orthography. The exact spelling of the state's name in the Hawaiian language is Hawaiʻi. In the Hawaii Admission Act that granted Hawaiian statehood, the federal government recognized Hawaii as the official state name. Official government publications, department and office titles, and the Seal of Hawaii use the traditional spelling with no symbols for glottal stops or vowel length. In contrast, the National and State Parks Services, the University of Hawaiʻi and some private enterprises implement these symbols. No precedent for changes to U.S. state names exists since the adoption of the United States Constitution in 1789. However, the Constitution of Massachusetts formally changed the Province of Massachusetts Bay to the Commonwealth of Massachusetts in 1780, and in the 1819 the Territory of Arkansaw was created but was later admitted to statehood as State of Arkansas.

Geography and environment

There are eight main Hawaiian islands, seven of which are permanently inhabited. The island of Niʻihau is privately managed by brothers Bruce and Keith Robinson; access is restricted to those who have permission from the island's owners.

Island Nickname Area Population(as of 2010) Density Highest point Elevation Age (Ma) Location Hawaiʻi The Big Island 1 4,028.0 sq mi (10,432.5 km2) 185,079 4 45.948/sq mi (17.7407/km2) Mauna Kea 1 13,796 ft (4,205 m) 0.4 19°34′N 155°30′W / 19.567°N 155.500°W / 19.567; -155.500 (Hawaii) Maui The Valley Isle 2 727.2 sq mi (1,883.4 km2) 144,444 2 198.630/sq mi (76.692/km2) Haleakalā 2 10,023 ft (3,055 m) 1.3–0.8 20°48′N 156°20′W / 20.800°N 156.333°W / 20.800; -156.333 (Maui) Oʻahu The Gathering Place 3 596.7 sq mi (1,545.4 km2) 953,207 1 1,597.46/sq mi (616.78/km2) Mount Kaʻala 5 4,003 ft (1,220 m) 3.7–2.6 21°28′N 157°59′W / 21.467°N 157.983°W / 21.467; -157.983 (Oahu) Kauaʻi The Garden Isle 4 552.3 sq mi (1,430.5 km2) 66,921 3 121.168/sq mi (46.783/km2) Kawaikini 3 5,243 ft (1,598 m) 5.1 22°05′N 159°30′W / 22.083°N 159.500°W / 22.083; -159.500 (Kauai) Molokaʻi The Friendly Isle 5 260.0 sq mi (673.4 km2) 7,345 5 28.250/sq mi (10.9074/km2) Kamakou 4 4,961 ft (1,512 m) 1.9–1.8 21°08′N 157°02′W / 21.133°N 157.033°W / 21.133; -157.033 (Molokai) Lānaʻi The Pineapple Isle 6 140.5 sq mi (363.9 km2) 3,135 6 22.313/sq mi (8.615/km2) Lānaʻihale 6 3,366 ft (1,026 m) 1.3 20°50′N 156°56′W / 20.833°N 156.933°W / 20.833; -156.933 (Lanai) Niʻihau The Forbidden Isle 7 69.5 sq mi (180.0 km2) 170 7 2.45/sq mi (0.944/km2) Mount Pānīʻau 8 1,250 ft (381 m) 4.9 21°54′N 160°10′W / 21.900°N 160.167°W / 21.900; -160.167 (Niihau) Kahoʻolawe The Target Isle 8 44.6 sq mi (115.5 km2) 0 8 0 Puʻu Moaulanui 7 1,483 ft (452 m) 1.0 20°33′N 156°36′W / 20.550°N 156.600°W / 20.550; -156.600 (Kahoolawe)

Topography

The Hawaiian archipelago is located 2,000 mi (3,200 km) southwest of the continental United States. Hawaii is the southernmost U.S. state and the second westernmost after Alaska. Hawaii, along with Alaska, does not border any other U.S. state. It is the only U.S. state that is not geographically located in North America, the only state completely surrounded by water and that is entirely an archipelago, and the only state in which coffee is cultivable.

In addition to the eight main islands, the state has many smaller islands and islets. Kaʻula is a small island near Niʻihau that is often overlooked. The Northwest Hawaiian Islands is a group of nine small, older islands to the northwest of Kauaʻi that extend from Nihoa to Kure Atoll; these are remnants of once much larger volcanic mountains. Across the archipelago are around 130 small rocks and islets, such as Molokini, which are either volcanic, marine sedimentary or erosional in origin.

Hawaii's tallest mountain Mauna Kea is 13,796 ft (4,205 m) above mean sea level; it is taller than Mount Everest if measured from the base of the mountain, which lies on the floor of the Pacific Ocean and rises about 33,500 feet (10,200 m).

Geology

The Hawaiian islands were formed by volcanic activity initiated at an undersea magma source called the Hawaii hotspot. The process is continuing to build islands; the tectonic plate beneath much of the Pacific Ocean continually moves northwest and the hot spot remains stationary, slowly creating new volcanoes. Because of the hotspot's location, all currently active land volcanoes are located on the southern half of Hawaii Island. The newest volcano, Lōʻihi Seamount, is located south of the coast of Hawaii Island.

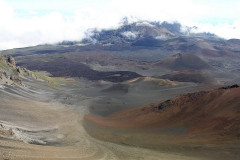

The last volcanic eruption outside Hawaii Island occurred at Haleakalā on Maui before the late 18th century, though it could have been hundreds of years earlier. In 1790, Kīlauea exploded; it was the deadliest eruption known to have occurred in the modern era in what is now the United States. Up to 5,405 warriors and their families marching on Kīlauea were killed by the eruption. Volcanic activity and subsequent erosion have created impressive geological features. Hawaii Island has the third-highest point among the world's islands.

On the flanks of the volcanoes, slope instability has generated damaging earthquakes and related tsunamis, particularly in 1868 and 1975. Steep cliffs have been created by catastrophic debris avalanches on the submerged flanks of ocean island volcanoes.

Flora and fauna

Because the islands of Hawaii are distant from other land habitats, life is thought to have arrived there by wind, waves (i.e. by ocean currents) and wings (i.e. birds, insects, and any seeds they may have carried on their feathers). This isolation, in combination with the diverse environment (including extreme altitudes, tropical climates, and arid shorelines), produced an array of endemic flora and fauna. Hawaii has more endangered species and has lost a higher percentage of its endemic species than any other U.S. state. One endemic plant, Brighamia, now requires hand-pollination because its natural pollinator is presumed to be extinct. The two species of Brighamia—B. rockii and B. insignis—are represented in the wild by around 120 individual plants. To ensure these plants set seed, biologists rappel down 3,000-foot (910 m) cliffs to brush pollen onto their stigmas.

The extant main islands of the archipelago have been above the surface of the ocean for fewer than 10 million years; a fraction of the time biological colonization and evolution have occurred there. The islands are well known for the environmental diversity that occurs on high mountains within a trade winds field. On a single island, the climate around the coasts can range from dry tropical (less than 20 inches or 510 millimetres annual rainfall) to wet tropical; on the slopes, envionments range from tropical rainforest (more than 200 inches or 5,100 millimetres per year), through a temperate climate, to alpine conditions with a cold, dry climate. The rainy climate impacts soil development, which largely determines ground permeability, affecting the distribution of streams and wetlands.

Antipodes

Hawaii is the only U.S. state that is antipodal to inhabited land. Most of the state lies opposite Botswana, though Niʻihau's antipode aligns with Namibia, and Kauaʻi's straddles the Botswana–Namibia border. This area of Africa near Maun, Botswana and Ghanzi includes nature reserves and small settlements near the Okavango Delta.

History

Part of a series on the History of Hawaii Timeline- Ancient

- Kingdom of Hawaii

- Provisional Government

- Republic of Hawaii

- U.S. Territory

- State of Hawaii

- v

- t

- e

Hawaii is one of four U.S. states—apart from the original thirteen—the Vermont Republic (1791), the Republic of Texas (1845), and the California Republic (1846)—that were independent nations prior to statehood. Along with Texas, Hawaii had formal, international diplomatic recognition as a nation.

The Kingdom of Hawaiʻi was sovereign from 1810 until 1893 when the monarchy was overthrown by resident American and European capitalists and landholders in a coup d'état. Hawaii was an independent republic from 1894 until August 12, 1898, when it officially became a territory of the United States. Hawaii was admitted as a U.S. state on August 21, 1959.

First human settlement – Ancient Hawaiʻi (800–1778)

Based on archaeological evidence, the earliest habitation of the Hawaiian Islands dates to around 300 CE, probably by Polynesian settlers from the Marquesas Islands. A second wave of migration from Raiatea and Bora Bora took place in the 11th century. The date of the human discovery and habitation of the Hawaiian Islands is the subject of academic debate. Some archaeologists and historians believe there was an early settlement from the Marquesas. They think it was a later wave of immigrants from Tahiti around 1000 CE who introduced a new line of high chiefs, the kapu system, the practice of human sacrifice, and the building of heiau. This later immigration is detailed in Hawaiian mythology (moʻolelo) about Paʻao. Other authors say there is no archaeological or linguistic evidence for a later influx of Tahitian settlers and that Paʻao must be regarded as a myth.

The history of the islands is marked by a slow, steady growth in population and the size of the chiefdoms, which grew to encompass whole islands. Local chiefs, called aliʻi, ruled their settlements, and launched wars to extend their influence and defend their communities from predatory rivals. Ancient Hawaii was a caste-based society, much like that of Hindus in India.

European arrival

It is possible that Spanish explorers arrived in the Hawaiian Islands in the 16th century—200 years before Captain James Cook's first documented visit in 1778. Ruy López de Villalobos commanded a fleet of six ships that left Acapulco in 1542 bound for the Philippines with a Spanish sailor named Juan Gaetano aboard as pilot. Depending on the interpretation, Gaetano's reports describe an encounter with either Hawaiʻi or the Marshall Islands. If de Villalobos' crew spotted Hawaiʻi, Gaetano would be considered the first European to see the islands. Some scholars have dismissed these claims due to a lack of credibility.

Spanish archives contain a chart that depicts islands at the same latitude as Hawaiʻi but with a longitude ten degrees east of the islands. In this manuscript, the island of Maui is named La Desgraciada (The Unfortunate Island), and what appears to be Hawaiʻi Island is named La Mesa (The Table). Islands resembling Kahoolawe, Lanai, and Molokai are named Los Monjes (The Monks). For two-and-a-half centuries, Spanish galleons crossed the Pacific from Mexico along a route that passed south of Hawaiʻi on their way to Manila. The exact route was kept secret to protect the Spanish trade monopoly against competing powers.

The 1778 arrival of British explorer James Cook was the first documented contact by a European explorer with Hawaii. Cook named the archipelago as the Sandwich Islands in honor of his sponsor John Montagu, 4th Earl of Sandwich. Cook published the islands' location and rendered the native name as Owyhee. This spelling lives on in Owyhee County, Idaho. It was named after three native Hawaiian members of a trapping party who went missing in that area. The Owyhee Mountains were also named for them.

Cook visited the Hawaiian Islands twice. As he prepared for departure after his second visit in 1779, a quarrel ensued as Cook took temple idols and fencing as "firewood", and a minor chief and his men took a ship's boat. Cook abducted the King of Hawaiʻi Island, Kalaniʻōpuʻu, and held him for ransom aboard his ship in order to gain return of Cook's boat. This tactic had worked in Tahiti and other islands. Instead, Kalaniʻōpuʻu's supporters fought back, killing Cook and four marines as Cook's party retreated along the beach to their ship. They departed without the ship's boat.

After Cook's visit and the publication of several books relating his voyages, the Hawaiian islands attracted many European visitors: explorers, traders, and eventually whalers, who found the islands to be a convenient harbor and source of supplies. Early British influence can be seen in the design of the flag of Hawaiʻi, which bears the Union Jack in the top-left corner. These visitors introduced diseases to the once-isolated islands, causing the Hawaiian population to drop precipitously. Native Hawaiians had no resistance to Eurasian diseases, such as influenza, smallpox and measles. By 1820, disease, famine and wars between the chiefs killed more than half of the Native Hawaiian population. During the 1850s, measles killed a fifth of Hawaii's people.

Historical records indicated the earliest Chinese immigrants to Hawaii originated from Guangdong Province; a few sailors arrived in 1778 with Captain Cook's journey and more arrived in 1789 with an American trader, who settled in Hawaii in the late 18th century. It appears that leprosy was introduced by Chinese workers by 1830; as with the other new infectious diseases, it proved damaging to the Hawaiians.

Kingdom of Hawaiʻi

House of KamehamehaDuring the 1780s and 1790s, chiefs often fought for power. After a series of battles that ended in 1795, all inhabited islands were subjugated under a single ruler, who became known as King Kamehameha the Great. He established the House of Kamehameha, a dynasty that ruled the kingdom until 1872.

After Kamehameha II inherited the throne in 1819, American Protestant missionaries to Hawaii converted many Hawaiians to Christianity. They used their influence to end many traditional practices of the people.[which?] The islands' first Christan king was Kamehameha III. Hiram Bingham I, a prominent Protestant missionary, was a trusted adviser to the monarchy during this period. Other missionaries and their descendants became active in commercial and political affairs, leading to conflicts between the monarchy and its restive American subjects. Catholic and Mormon missionaries were also active in the kingdom, but they converted a minority of the Native Hawaiian population. Missionaries from each major group administered to the leper colony at Kalaupapa on Molokaʻi, which was established in 1866 and operated well into the 20th century. The best known were Father Damien and Mother Marianne Cope, both of whom were canonized in the early 21st century as Roman Catholic saints.

The death of the bachelor King Kamehameha V—who did not name an heir—resulted in the popular election of Lunalilo over Kalākaua. Lunalilo died the next year, also without naming an heir. In 1874, the election was contested within the legislature between Kalākaua and Emma, Queen Consort of Kamehameha IV. After riots broke out, the United States and Britain landed troops on the islands to restore order. Governance passed to the House of Kalākaua.[clarification needed]

1887 Constitution and overthrow preparationsIn 1887, Kalākaua was forced to sign the 1887 Constitution of the Kingdom of Hawaii. Drafted by white businessmen and lawyers, the document stripped the king of much of his authority. It established a property qualification for voting that effectively disenfranchised most Hawaiians and immigrant laborers and favored the wealthier, white elite. Resident whites were allowed to vote but resident Asians were not. Because the 1887 Constitution was signed under threat of violence, it is known as the Bayonet Constitution. King Kalākaua, reduced to a figurehead, reigned until his death in 1891. His sister, Queen Liliʻuokalani, succeeded him; she was the last monarch of Hawaiʻi.

In 1893, Queen Liliʻuokalani announced plans for a new constitution. On January 14, 1893, a group of mostly Euro-American business leaders and residents formed the Committee of Safety to stage a coup d'état against the kingdom and seek annexation by the United States. United States Government Minister John L. Stevens, responding to a request from the Committee of Safety, summoned a company of U.S. Marines. According to historian William Russ, these troops effectively rendered the monarchy unable to protect itself.

Overthrow of 1893—the Republic of Hawaii (1894–1898)

In January 1893, Queen Liliʻuokalani was overthrown and replaced by a provisional government composed of members of the American Committee of Safety. American lawyer Sanford B. Dole became President of the Republic when the Provisional Government of Hawaii ended on July 4, 1894. Controversy ensued in the following years as the Queen tried to regain her throne. The administration of President Grover Cleveland commissioned the Blount Report, which concluded that the removal of Liliʻuokalani had been illegal. The U.S. government first demanded that Queen Liliʻuokalani be reinstated, but the Provisional Government refused.

Congress conducted an independent investigation, and on February 26, 1894, submitted the Morgan Report, which found all parties, including Minister Stevens—with the exception of the Queen—"not guilty" and not responsible for the coup. Partisans on both sides of the debate questioned the accuracy and impartiality of both the Blount and Morgan reports over the events of 1893.

In 1993, the US Congress passed a joint Apology Resolution regarding the overthrow; it was signed by President Bill Clinton. The resolution apologized for the overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom and acknowledged that the United States had annexed Hawaii unlawfully.

Annexation—the Territory of Hawaii (1898–1959)

After William McKinley won the 1896 U.S. presidential election, advocates pressed to annex the Republic of Hawaii. The previous president, Grover Cleveland, was a friend of Queen Liliʻuokalani. McKinley was open to persuasion by U.S. expansionists and by annexationists from Hawaiʻi. He met with three annexationists: Lorrin A. Thurston, Francis March Hatch and William Ansel Kinney. After negotiations in June 1897, Secretary of State John Sherman agreed to a treaty of annexation with these representatives of the Republic of Hawaii. The U.S. Senate never ratified the treaty. Despite the opposition of most native Hawaiians, the Newlands Resolution was used to annex the Republic to the U.S.; it became the Territory of Hawaii. The Newlands Resolution was passed by the House on June 15, 1898, by 209 votes in favor to 91 against, and by the Senate on July 6, 1898, by a vote of 42 to 21.

In 1900, Hawaii was granted self-governance and retained ʻIolani Palace as the territorial capitol building. Despite several attempts to become a state, Hawaii remained a territory for sixty years. Plantation owners and capitalists, who maintained control through financial institutions such as the Big Five, found territorial status convenient because they remained able to import cheap, foreign labor. Such immigration and labor practices were prohibited in many states.

Puerto Rican immigration to Hawaii began in 1899 when Puerto Rico's sugar industry was devastated by two hurricanes, causing a worldwide shortage of sugar and a huge demand for sugar from Hawaii. Hawaiian sugarcane plantation owners began to recruit experienced, unemployed laborers in Puerto Rico. Two waves of Korean immigration to Hawaii occurred in the 20th century. The first wave arrived between 1903 and 1924; the second wave began in 1965 after President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 into law.

Oʻahu was the target of a surprise attack on Pearl Harbor by Imperial Japan on December 7, 1941. The attack on Pearl Harbor and other military and naval installations, carried out by aircraft and by midget submarines, brought the United States into World War II.

Culture

The aboriginal culture of Hawaii is Polynesian. Hawaii represents the northernmost extension of the vast Polynesian Triangle of the south and central Pacific Ocean. While traditional Hawaiian culture remains as vestiges in modern Hawaiian society, there are re-enactments of the ceremonies and traditions throughout the islands. Some of these cultural influences, including the popularity (in greatly modified form) of lūʻau and hula, are strong enough to affect the wider United States.

Cuisine

The cuisine of Hawaii is a fusion of many foods brought by immigrants to the Hawaiian Islands, including the earliest Polynesians and Native Hawaiian cuisine, and American, Chinese, Filipino, Japanese, Korean, Polynesian and Portuguese origins. Plant and animal food sources are imported from around the world for agricultural use in Hawaii. Poi, a starch made by pounding taro, is one of the traditional foods of the islands. Many local restaurants serve the ubiquitous plate lunch, which features two scoops of rice, a simplified version of American macaroni salad and a variety of toppings including hamburger patties, a fried egg, and gravy of a loco moco, Japanese style tonkatsu or the traditional lūʻau favorites, including kālua pork and laulau. Spam musubi is an example of the fusion of ethnic cuisine that developed on the islands among the mix of immigrant groups and military personnel. In the 1990s, a group of chefs developed Hawaii regional cuisine as a contemporary fusion cuisine.

Customs and etiquette

Some key customs and etiquette in Hawaii are as follows: when visiting a home, it is considered good manners to bring a small gift for one's host (for example, a dessert). Thus, parties are usually in the form of potlucks. Most locals take their shoes off before entering a home. It is customary for Hawaiian families, regardless of ethnicity, to hold a luau to celebrate a child's first birthday. It is also customary at Hawaiian weddings, especially at Filipino weddings, for the bride and groom to do a money dance (also called the pandanggo). Print media and local residents recommend that one refer to non-Hawaiians as "locals of Hawaii" or "people of Hawaii".

Hawaiian mythology

Hawaiian mythology comprises the legends, historical tales, and sayings of the ancient Hawaiian people. It is considered a variant of a more general Polynesian mythology that developed a unique character for several centuries before about 1800. It is associated with the Hawaiian religion, which was officially suppressed in the 19th century but was kept alive by some practitioners to the modern day. Prominent figures and terms include Aumakua, the spirit of an ancestor or family god and Kāne, the highest of the four major Hawaiian deities.

Polynesian mythology

Polynesian mythology is the oral traditions of the people of Polynesia, a grouping of Central and South Pacific Ocean island archipelagos in the Polynesian triangle together with the scattered cultures known as the Polynesian outliers. Polynesians speak languages that descend from a language reconstructed as Proto-Polynesian that was probably spoken in the area around Tonga and Samoa in around 1000 BCE.

Prior to the 15th century, Polynesian people migrated east to the Cook Islands, and from there to other island groups such as Tahiti and the Marquesas. Their descendants later discovered the islands Tahiti, Rapa Nui and later the Hawaiian Islands and New Zealand.

The Polynesian languages are part of the Austronesian language family. Many are close enough in terms of vocabulary and grammar to be mutually intelligible. There are also substantial cultural similarities between the various groups, especially in terms of social organization, childrearing, horticulture, building and textile technologies. Their mythologies in particular demonstrate local reworkings of commonly shared tales. The Polynesian cultures each have distinct but related oral traditions; legends or myths are traditionally considered to recount ancient history (the time of "pō") and the adventures of gods ("atua") and deified ancestors.

List of state parks

There are many Hawaiian state parks.

- The Island of Hawaiʻi has state parks, recreation areas, and historical parks.

- Kauaʻi has the Ahukini State Recreation Pier, six state parks, and the Russian Fort Elizabeth State Historical Park.

- Maui has two state monuments, several state parks, and the Polipoli Spring State Recreation Area. Moloka‘i has the Pala'au State Park. *Oʻahu has several state parks, a number of state recreation areas, and a number of monuments, including the Ulu Pō Heiau State Monument.

Music

The music of Hawaii includes traditional and popular styles, ranging from native Hawaiian folk music to modern rock and hip hop. Hawaii's musical contributions to the music of the United States are out of proportion to the state's small size. Styles such as slack-key guitar are well-known worldwide, while Hawaiian-tinged music is a frequent part of Hollywood soundtracks. Hawaii also made a major contribution to country music with the introduction of the steel guitar.

Traditional Hawaiian folk music is a major part of the state's musical heritage. The Hawaiian people have inhabited the islands for centuries and have retained much of their traditional musical knowledge. Their music is largely religious in nature, and includes chanting and dance music. Hawaiian music has had an enormous impact on the music of other Polynesian islands; according to Peter Manuel, the influence of Hawaiian music a "unifying factor in the development of modern Pacific musics".

Tourism

Tourism is an important part of the Hawaiian economy. In 2003, according to state government data, there were over 6.4 million visitors, with expenditures of over $10 billion, to the Hawaiian Islands. Due to the mild year-round weather, tourist travel is popular throughout the year. The major holidays are the most popular times for outsiders to visit, especially in the winter months. Substantial numbers of Japanese tourists still visit the islands but have now been surpassed by Chinese and Koreans due to the collapse of the value of the Yen and the weak Japanese economy. The average Japanese stays only 5 days while other Asians spend over 9.5 days and spend 25% more.

Hawaii hosts numerous cultural events. The annual Merrie Monarch Festival is an international Hula competition. The Hawaii International Film Festival is the premier film festival for Pacific rim cinema. Honolulu hosts the state's long-running LGBT film festival, the Rainbow Film Festival.

Health

As of 2009, Hawaii's health care system insures 92% of residents. Under the state's plan, businesses are required to provide insurance to employees who work more than twenty hours per week. Heavy regulation of insurance companies helps reduce the cost to employers. Due in part to heavy emphasis on preventive care, Hawaiians require hospital treatment less frequently than the rest of the United States, while total health care expenses measured as a percentage of state GDP are substantially lower. Proponents of universal health care elsewhere in the U.S. sometimes use Hawaii as a model for proposed federal and state health care plans.

Transportation

A system of state highways encircles each main island. Only Oʻahu has federal highways, and is the only area outside the contiguous 48 states to have signed Interstate highways. Narrow, winding roads and congestion in populated places can slow traffic. Each major island has a public bus system.

Honolulu International Airport (IATA: HNL), which shares runways with the adjacent Hickam Field (IATA: HIK), is the major commercial aviation hub of Hawaii. The commercial aviation airport offers intercontinental service to North America, Asia, Australia and Oceania. Hawaiian Airlines, Mokulele Airlines and go! use jets to provide services between the large airports in Honolulu, Līhuʻe, Kahului, Kona and Hilo. Island Air and Pacific Wings serve smaller airports. These airlines also provide air freight services between the islands.

Until air passenger services began in the 1920s, private boats were the sole means of traveling between the islands. Seaflite operated hydrofoils between the major islands in the mid-1970s.

The Hawaii Superferry operated between Oʻahu and Maui between December 2007 and March 2009, with additional routes planned for other islands. Protests and legal problems over environmental impact statements ended the service, though the company operating Superferry has expressed a wish to recommence ferry services in the future. Currently there are passenger ferry services in Maui County between Molokaʻi and Maui, and between Lanaʻi and Maui, though neither of these take vehicles. Currently Norwegian Cruise Lines and Princess Cruises provide passenger cruise ship services between the larger islands.

Rail

At one time Hawaii had a network of railroads on each of the larger islands that transported farm commodities and passengers. Most were 3 ft (914 mm) narrow gauge systems but there were some 2 ft 6 in (762 mm) gauge on some of the smaller islands. The standard gauge in the U.S. is 4 ft 8 1⁄2 in (1,435 mm). By far the largest railroad was the Oahu Railway and Land Company (OR&L) that ran lines from Honolulu across the western and northern part of Oahu.

The OR&L was important for moving troops and goods during World War II. Traffic on this line was busy enough for signals to be used to facilitate movement of trains and to require wigwag signals at some railroad crossings for the protection of motorists. The main line was officially abandoned in 1947, although part of it was bought by the U.S. Navy and operated until 1970. Thirteen miles (21 km) of track remain; preservationists occasionally run trains over a portion of this line. The Honolulu High-Capacity Transit Corridor Project aims to add elevated passenger rail on Oahu to relieve highway congestion.

Legal status of Hawaii

While Hawaii is internationally recognized as a state of the United States of America while also being broadly accepted as such in mainstream understanding, the legality of this status has been raised in U.S. District Court, the U.N., and other international forums. Domestically, the debate is a topic covered in the Kamehameha Schools curriculum. On September 29, 2015 the Department of the Interior announced a procedure to recognize a Native Hawaiian government.

Hawaiian sovereignty movement

Political organizations seeking some form of sovereignty for Hawaii have been active since the 1880s. Generally, their focus is on self-determination and self-governance, either for Hawaii as an independent nation (in many proposals, for "Hawaiian nationals" descended from subjects of the Hawaiian Kingdom or declaring themselves as such by choice), or for people of whole or part native Hawaiian ancestry in an indigenous "nation to nation" relationship akin to tribal sovereignty with US federal recognition of Native Hawaiians.

Some groups also advocate some form of redress from the United States for the 1893 overthrow of Queen Liliʻuokalani, and for what is described as a prolonged military occupation beginning with the 1898 annexation. The movement generally views both the overthrow and annexation as illegal, with the Apology Resolution passed by US Congress in 1993 cited as a major impetus by the movement for Hawaiian sovereignty. The sovereignty movement considers Hawaii to be an illegally occupied nation.